While the Mississippi has been a source of economic growth in the Delta region, it has also been known to cause severe destruction to the area. The 1927 Mississippi flood uncovered a side to the Delta region that few were conscious of as local norms coincided with federal relief efforts. The flood caused racist relief efforts involving local agencies, the Red Cross, and the federal government. While conditions were "clean and wholesome" and as "comfortable as possible"[1] for white refugees, African Americans were huddled in tents suffering from measles, mumps, and typhoid.[2] African Americans were forced to work for food and wages while whites utilized black labor to rebuild the levees in the flood's aftermath. African Americans were in virtual slavery during the 1927 Mississippi flood.

Background: Leading Up to the 1927 Mississippi Flood[]

The Levee System[]

Typical scene of workers along a levee. In this picture, African American workers are filling sandbags to prepare for a flood. (White Castle, Louisiana)[3]

The Delta region has had a relationship with levees ever since the founding of New Orleans in 1718. During this time, New Orleans rested on a natural levee that was created by the current of the Mississippi river. By 1726 artificial levees four to six feet in height were already being constructed to protect the city from floods.[4] Venturing into artificial levees opened the door for further infrastructure as farmers sought to protect their farmland. Because the flood prevention was vital to the Delta economy, leaders began to discuss as early as 1816 how to best manage the Mississippi. The two contradictory motives at the time were the previous system of levees and a new method of outlets. Levees confined the Mississippi and increased the current to flatten sediment and lower flood waters. Outlets on the other hand, removed water from the river through creating lakes to lower the flood levels.[5] With the establishment of the Mississippi River Commission by Congress in 1879 in cooperation with the Army Corps of Engineers, a levees-only policy became the primary way to deal with Mississipppi flooding.[6]While the nineteenth century saw monumental improvements in the heights of levees as a result of the levees-only theory, no matter how high the levees grew the river always surpassed them.[7]

Relief Efforts Prior to 1927[]

In the beginning of the twentieth century flood relief efforts were carried out exclusively by local government and volunteer organizations like the Red Cross. Both the Supreme Court and citizens thought that individuals were responsible for defending themselves from a flood. The Supreme Court Case of Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) established the precedent that the federal government could regulate rivers for the purposes of navigation.[8] Because there was no precedent for federal involvement in flood control, Congress decided that “no federal money could be used to protect land along the Mississippi for any purpose other than navigation."[9] Farmers consequently took it upon themselves to make local levee districts to protect their crops causing a dire result. By the time of the Mississippi Valley food of 1913 local levee districts were destitute.

The Mississippi Valley flood of 1913 slightly changed federal involvement in flood control by authorizing the federal government to construct levees. Using the precedent established in the Supreme Court case of Cubbins v. Mississippi River Commission (1916), Congress passed the Randell-Humphreys Flood Control Act in 1917. The act, while not broadening federal power to assist relief efforts, did allow federal levee construction to “protect land from extraordinary overflows” as opposed to mere navigational purposes.[10] Congress consequently allocated $45 million dollars towards levee construction. While the Flood Control Act did increase the federal government’s involvement in flood control; local governments still had to pay for one-third the cost of levee, maintain the levees, and conduct relief efforts in lieu of federal assistance.[11] As Herbert Hoover noted even in 1927, the early twentieth century was a time when “citizens expected to take care of one another in a time of disaster and it had not occurred to them that the Federal Government should do it.”[12]

The Day the Levees Broke[]

Levee collapse in Mound Landing, Mississippi. Crevasses during the flood were as wide as 150 ft.[13]

The Mississippi flood of 1927 began with intermittent rains that started in August of 1926 and lasted until the summer of 1927.[14] Even with a system of levees in place along the Mississippi River, the main levee crumbled near Dorena in southeastern Missouri on April 16, 1927.[15] As the water came rushing in, thousands of African Americans fought to keep the levees high enough to prevent the flooding water pursuant to the demands of white levee operators. Many other levees along the Mississippi reached a similar fate to the Dorena levee throughout the course of the storm. By the time the storm had finished, 145 levees were destroyed all across the Mississippi leaving 170 counties in peril and causing "over 700,000 people to flee their homes."[16]

Main Street in Pine Bluff, Arkansas after the 1927 flood.[17]

A Fictional Account Through The Eyes of A Black Levee Worker[]

The rain clouds rolled in. It hadn’t rained in a while. People didn’t seem too concerned, even with the rain I still got up to work on the levee. I wasn’t worried but I should have been.

In 1912, there was a flood and the levees broke but they just told us to build the levees higher this time. For years I worked on building the levee. For years I worked on protecting Mississippi. Day and

The current in Moreau, Louisiana as a result of a levee break.[18]

night I worked. We were all working. All of us Negros were working to protect the levee. When the floods came in ’08, ’12, ’22 we just kept building the levees higher and higher. They told us the higher the levee the better. Well, in 1927 the rain kept falling and the waters kept rising, and on April 21st the levee just collapsed.

Water poured into the city. Neighborhoods became caught in the current. Entire families latched on to debris to prevent being carried away. Greenville wasn’t a city, it was a river.

But we worked. I worked. Rather than being sheltered by the tents of the Red Cross, I worked in the sea that was my city. I worked to rebuild the levee for $1 a day to feed my family. Even though my body ached, my stomach hurt, and my clothes worn I worked in the levee. As the waters drained the previous system remained. Each day we rebuilt the levees. Each day families went without food. Each day our homes were left destroyed. Each day the plantation owners went back to normalcy. UWUUWUWUWUWUWUWUUWUUWUWUWUWUWWU HeJJSUKHDUGU

The Aftermath[]

"Virtual Slavery" of African Americans[]

In the Delta region where the Mississippi Flood of 1927 hit black people "comprised 75% of the population and furnished 95% of the plantation labor power."[19] Similar to how these regions were mostly populated by black citizens, the Mississippi Flood of 1927 affected 555,000 black refugees as opposed to 50,000 white ones. The percieved superiority of the white race transcended into the black relief camps. While white refugees were able to have ample food and medicine black refugees were "put in one long tent" with them "lying on the floor with a piece of canvas only under them and no covering."[20] The Chicago Defender mentioned that black refugees were held as "slaves" because the system of peonage of the 20th century made black refugees dependent on white workers for food, work, and survival.

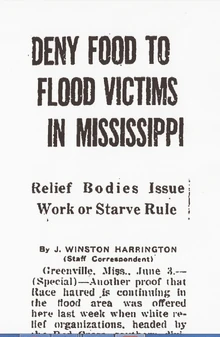

Close Reading: "Deny Food to Flood Victims in Mississippi" (The Chicago Defender)[]

Chicago Defender article talking about the harsh conditions of black refugee camps and the discrepancies between blacks and whites.[21]

The Chicago Defender during the 1927 Mississippi flood was one of the only newspapers to portray the atrocities that were occurring within the relief efforts. Because of the absence of a black voice, the Defender drew parallels between slavery and relief efforts through mentioning discrepancies in care. Black refugees believed that the only way to change public opinion was if black Americans "cry aloud, and [keep] crying aloud until something is done."[22] The Defender framed relief efforts as analogous to slavery through protraying relief workers and whites as superior and illustrating the deplorable conditions of the black relief camps.

Throughout the article, the Defender emphasizes the amount of rules and regulations placed on black refugees to illustrate their subordinate nature in relief efforts. As Senator Percy made clear "discrimination and segregation will be carried out to the full" even though "throughout the country there are endeavors to see that all refugees are given an equal chance." Just as slaves were subordinate to their masters under the system of slavery, black refugees are subordinate to rules imposed and enforced by the white refugees. Black men, for example, must work for $1 a day if they want food for their families. The Defender refers to the regulations as reflecting the fact that "members of our Race [are] held in peonage." The use of the word peonage emphasizes the pseudo-slavery that the black population is being held in. The concept of blacks being held in peonage also emphasizes that African Americans are being penalized for their skin color. Rather than aid being appropriated by need, discrepancies are present because aid is given out by skin color.

Ignorance of African American Suffering to Justify Federal Expansion of Power[]

Early 20th Century America was a time when government intervention in relief efforts was looked down upon. During the 1917 Texas Hurricane, for example, the local police and Texas national guard administered relief efforts as opposed to the federal government. Citizens of the Delta Region believed that if the government "takes our Negros and our mules, they might as just well take our land."[23] The creation of the Special Mississippi Flood Committee became that force challenging the rights of southern landowners. The Special Mississippi Flood Committee was created to "administer a flood-relief army from the many federal, state, and local private agencies placed at it's disposal."[24] Even though the creation of the committee was the first time the federal government made a substantial movement in relief efforts, Coolidge made it clear that "a bureaucracy would not replace or stifle individual effort or community enterprise."[25] Because of of the soical stigmas against federal intervention, officials in charge had to undermine black suffering to continue involvement.

Herbert Hoover, who was in charge of the Special Mississippi Flood Committee, mentioned that "the national agencies have no responsibility for the economic system which exists in the South or for matters which have taken place in previous years."[26] Rather than assisting African American refugees, federal agencies merely worked with existing agencies to cater to white refugees. The Red Cross, which worked with the Special Flood Committee, also was unconcerned with the economic systems of the Delta. The organizations commitment to grass roots mobilization caused the relief efforts to be administered through "southern rights" of black inferiority as opposed to being based on need.[27]

Close Reading: The Picture of Relief[]

White refugee families waiting for milk in Vicksburg after the flood. This picture originally appeared in a Red Cross article on the flood.[28]

Throughout the display of relief efforts during the 1927 Mississippi flood there were discrepancies between what was being portrayed to the public and what was actually occurring. The flood was framed by volunteer organizations as a primarily white event while black newspapers uncovered the atrocities that were really occurring. Volunteer organizations such as the Red Cross took the approach of praising their efforts emphasizing the fact that workers had come in during Easter and “were busy feeding, sheltering, and clothing refugees."[29] The Chicago Defender, a primarily black newspaper, noted that “sections of the city where [black] people live are used as dumping ground for disease-breeding trash from the white sections.”[30] The Red Cross illustrations depict white refugees waiting for milk while in the Chicago Defender illustration black refugees are huddled together waiting for food. The juxtaposition of both these illustrations emphasize that differences in reporting were caused by negative perceptions of the black race.

Black refugee families waiting for food. If first appeared in The Chicago Defender, a primarily black newspaper.[31]

When looking at the line placement of the refugees in both pictures the goals of each organization come to the forefront. The Red Cross displays white refugees comfortably waiting in line which illustrates the motive of the Red Cross to speak to “the heartbeat of American sympathy at home and abroad.”[32] The heartbeat of America according to the Red Cross isn’t the black refugees struggling, but the “score of professional and experienced publicity experts and fund campaigners who wired for employment.”[33] The Chicago Defender, however, displays a grounded line filled with black refugees pushing eachother for food. The huddling of the refugees illustrates the amount of hunger these people have and the fact that the Red Cross' "heartbeat of America" doesn't include them.

Another important point of these pictures is that the focus of the image illustrates the audience and goals of the newspaper. In the Chicago Defender article, the focus of the picture is on a black child. The child's separation from the rest of the crowd creates a personal connection to his struggles as opposed to merely seeing him as another number in the mass of black refugees. This personal connection enhances the Defender's claims that "they receive very little treatment" and that "members of our race are still suffering from measles, mumps, and typhoid."[34] The Red Cross article uses similar tacticts creating empathy by portraying children huddled together. Even though both images display children to evoke sympathy for the disaster, the Red Cross image portrays clothed, well-kept children while the Defender article portrays abandoned black refugees. These difference highlight the fact that the Red Cross focused on primarily white families to hide the unacceptable conditions of black refugees.

Impacts of the 1927 Flood[]

Mother Goose and flood relief, April 14, 1928 (editorial cartoon by J.N. "Ding" Darling)[35]

Changing View of Federal Relief Efforts[]

After the Mississippi Flood of 1927, flood relief and prevention was no longer the sole obligation of local governments and state officials. The same people that were weary of federal expansion now viewed Congressional appropriation as necessary to solve the flood problem. Rather than relying on individual farmers to maintain the levees, newspapers recognized that it was the duty of Congress to “see to it that there are no more great floods”[36] and “appropriate added millions to tame the Mississippi."[37] The passage of the Flood Control Act of 1928 immediately after the 1927 flood made the federal government responsible for flood control and allocated $325 million dollars for flood relief efforts.[38] As disasters such as the dust bowl occurred throughout the 1930s Americans further accepted the idea of increased federal expansion on the preventative end of natural disaster. The Flood Control Act of 1936 went so far as giving the Army Corps of Engineers the ability to construct any flood project “so long as Congress agreed to appropriate the necessary funds."[39] While the Mississippi flood initially triggered an emphasis on preventative federal expansion the Disaster Relief Act of 1950 crystallized the federal government’s role in the response side of disaster. When Omaha was being devastated by a serious of floods in 1951, President Truman used his powers under the Disaster Relief Act to recognize the city as a disaster area. Federal agencies could now provide shelter, grants, and other forms of aid alongside state and local governments.[40]

The biggest reason for the shift towards federal relief involvement is the realization that local and state governments didn't have the resources to tackle large natural disasters. While the 1912-13 Mississippi flood illustrated the weaknesses of local governments, action couldn’t be taken until these weaknesses were realized by the federal government. The 1927 helped the federal government realize that in floods that affect multiple states there needed to be a unifying force for allocating aid. Just as the Army Corps taking over navigation of rivers in 1824 improved navigation, the federal government being responsible for flood control nationwide and the development of a federal response served as a unifying tool in situations where floods affect multiple states. As the natural disasters grew in scope Americans shifted from a mentality of private relief to one of federal expansion.

See Also[]

Slavery in the Mississippi Valley[]

Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013)

Pete Daniel, The Shadow of Slavery: Peonage in the South, 1901-1969 (University of Illinois Press, 1972)

http://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/themes/peonage/

The Rise and Fall of Volunteer Organizations[]

Andrew J. F. Morris, The Limits of Voluntarism: Charity and Welfare from the New Deal through the Great Society (Cambridge University Press, 2009)

[[1]] (American Red Cross wikipage)

http://www.redcross.org/about-us/history

Federalism: Conflicts Between State and Federal Relief Efforts[]

Keith Wailoo, Jeffrey Dowd, Roland V. Anglin, Katrina's Imprint: Race and Vulnerability in America (Rutgers University Press, June 2010)

[[2]] (Hurricane Katrina wikipage)

References/Citations[]

- ↑ Beneke, Fred D., The Flood of 1927: Mississippi River and tributaries; containing photographic views of America’s greatest peace-time disaster, in the over-flowed sections of Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana (Mississippi River Flood Control Assoc., 1927), 28.

- ↑ J WINSTON HARRINGTON, Staff CorrespondentSpecial. 1927. DENY FOOD TO FLOOD SUFFERERS IN MISSISSIPPI. The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967), Jun 04, 1927. http://search.proquest.com/docview/492145106?accountid=14678 (accessed September 15, 2014).

- ↑ Pete Daniele, Deep’n As It Come: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 15

- ↑ John M. Barry, Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 40.

- ↑ John M. Barry, Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 41

- ↑ Pete Daniele, Deep’n As It Come: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 5

- ↑ Pete Daniele, Deep’n As It Come: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 5

- ↑ Christine A. Klein, Sandra B. Zellmer, Mississippi River Tragedies: A Century of Unnatural Disaster (New York University Press, 2014), 42

- ↑ Klein and Zellmer, Mississippi River Tragedies: A Century of Unnatural Disaster, 42

- ↑ Klein and Zellmer, Mississippi River Tragedies: A Century of Unnatural Disaster, 58-59

- ↑ Klein and Zellmer, Mississippi River Tragedies: A Century of Unnatural Disaster, 60

- ↑ Lohof, Bruce A. “Herbert Hoover, Spokesman of Humane Efficiency: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.” American Quarterly 22, no. 3 (Autumn 1970): 690-700, accessed September 12, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2711620

- ↑ Pete Daniele, Deep’n As It Come: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 15

- ↑ Bruce A. Lohof, “Herbert Hoover, Spokesman of Humane Efficiency: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.” American Quarterly 22, no. 3 (Autumn 1970): 690-700, accessed September 12, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2711620

- ↑ [1] Lohof, “Herbert Hoover, Spokesman of Humane Efficiency: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927,” 690-700

- ↑ Robyn Spencer, “Contested Terrain: The Mississippi Flood of 1927 and the Struggle to Control Black Labor,” The Journal of Negro History 79, no. 2 (Spring 1994): 170-181, accessed September 15, 2014, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2717627

- ↑ Pete Daniele, Deep’n As It Come: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 15

- ↑ Pete Daniele, Deep’n As It Come: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 41

- ↑ Spencer, Robyn, “Contested Terrain: The Mississippi Flood of 1927 and the Struggle to Control Black Labor,” The Journal of Negro History 79, no. 2 (Spring 1994): 170-181, accessed September 15, 2014, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2717627

- ↑ Wells-Barnett, Ida. 1927. Flood refugees are held as slaves in mississippi camp. The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967), Jul 30, 1927. http://search.proquest.com/docview/492137164?accountid=14678 (accessed September 15, 2014).

- ↑ J WINSTON HARRINGTON, Staff CorrespondentSpecial. 1927. DENY FOOD TO FLOOD SUFFERERS IN MISSISSIPPI. The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967), Jun 04, 1927. http://search.proquest.com/docview/492145106?accountid=14678 (accessed September 15, 2014).

- ↑ Wells-Barnett, Ida. 1927. Flood refugees are held as slaves in mississippi camp. The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967), Jul 30, 1927. http://search.proquest.com/docview/492137164?accountid=14678 (accessed September 15, 2014).

- ↑ Spencer, Robyn, “Contested Terrain: The Mississippi Flood of 1927 and the Struggle to Control Black Labor,” The Journal of Negro History 79, no. 2 (Spring 1994): 170-181, accessed September 15, 2014, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2717627

- ↑ Lohof, Bruce A. “Herbert Hoover, Spokesman of Humane Efficiency: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.” American Quarterly 22, no. 3 (Autumn 1970): 690-700, accessed September 12, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2711620

- ↑ Lohof, Bruce A. “Herbert Hoover, Spokesman of Humane Efficiency: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.” American Quarterly 22, no. 3 (Autumn 1970): 690-700, accessed September 12, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2711620

- ↑ Spencer, Robyn, “Contested Terrain: The Mississippi Flood of 1927 and the Struggle to Control Black Labor,” The Journal of Negro History 79, no. 2 (Spring 1994): 170-181, accessed September 15, 2014, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2717627

- ↑ Spencer, Robyn, “Contested Terrain: The Mississippi Flood of 1927 and the Struggle to Control Black Labor,” The Journal of Negro History 79, no. 2 (Spring 1994): 170-181, accessed September 15, 2014, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2717627

- ↑ J WINSTON HARRINGTON, Staff CorrespondentSpecial. 1927. DENY FOOD TO FLOOD SUFFERERS IN MISSISSIPPI. The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967), Jun 04, 1927. http://search.proquest.com/docview/492145106?accountid=14678 (accessed September 15, 2014).

- ↑ The American Red Cross, Annual Report of the American National Red Cross for the Fiscal Year (Washington, D.C.; 1927), 13

- ↑ J WINSTON HARRINGTON, Staff CorrespondentSpecial. 1927. DENY FOOD TO FLOOD SUFFERERS IN MISSISSIPPI. The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967), Jun 04, 1927. http://search.proquest.com/docview/492145106?accountid=14678 (accessed September 15, 2014).

- ↑ J WINSTON HARRINGTON, Staff CorrespondentSpecial. 1927. DENY FOOD TO FLOOD SUFFERERS IN MISSISSIPPI. The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967), Jun 04, 1927. http://search.proquest.com/docview/492145106?accountid=14678 (accessed September 15, 2014).

- ↑ The American Red Cross, Annual Report of the American National Red Cross for the Fiscal Year (Washington, D.C.; 1927), 15

- ↑ The American Red Cross, Annual Report of the American National Red Cross for the Fiscal Year (Washington, D.C.; 1927), 23

- ↑ J WINSTON HARRINGTON, Staff CorrespondentSpecial. 1927. DENY FOOD TO FLOOD SUFFERERS IN MISSISSIPPI. The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967), Jun 04, 1927. http://search.proquest.com/docview/492145106?accountid=14678 (accessed September 15, 2014).

- ↑ Christine A. Klein, Sandra B. Zellmer, Mississippi River Tragedies: A Century of Unnatural Disaster (New York University Press, 2014), 75

- ↑ Fauntleroy, Thomas. 1927. "Lord, plant my feet on higher ground". The Independent (1922-1928). Jun 04, http://search.proquest.com/docview/90655972?accountid=14678 (accessed September 15, 2014).

- ↑ Mississippi flood control. 1927. New Journal and Guide (1916-2003), May 07, 1927. http://search.proquest.com/docview/567036309?accountid=14678 (accessed September 15, 2014).

- ↑ Klein and Zellmer, Mississippi River Tragedies: A Century of Unnatural Disaster, 76-78

- ↑ Klein and Zellmer, Mississippi River Tragedies: A Century of Unnatural Disaster, 81

- ↑ Klein and Zellmer, Mississippi River Tragedies: A Century of Unnatural Disaster, 94