In July of 1995, an invisible sweltering sheet covered Chicago. Although unable to see with the human eye, the heat wave, characterized by an intense combination of heat and humidity, presented a lethal force responsible for the death of more than 700 unassuming Chicago citizens. Due to the lack of information and warning for heat waves, they often go unnoticed and underreported, leaving them responsible for more deaths than any other natural disaster.[1] In a city plagued by government corruption and apathy regarding racial inequality, the effects of the Chicago heat wave were unequally distributed — leaving the poor, elderly African-American population at the highest level of risk.[2] The predominately African-American community of Englewood on Chicago’s South Side was hit harder than any other singular area.[3] The Chicago heat wave of 1995 was not a natural disaster, but rather a culmination of deep-seated, race-based, economic inequality in Chicago — both prior to and during 1995.

Background on the Heat Wave

Following World War II, America emerged as a superpower. With this newfound international recognition came changes within society. Technology radically changed the way many Americans lived. With the introduction of interstate highways as well as a boom in the number of automobiles produced, for the first time many Americans were relocating from the city to the suburbs. The post-World War II baby boom and large influx of immigrants also contributed to this shift in way of life. In turn, insufficient housing, low wages, and non-white ethnic makeup characterized inner cities. The people of the inner city became virtually invisible to middle America.

During this period Chicago experienced the growth of predominately white neighborhoods and a significant population decline in predominately African-American neighborhoods.[4] A 1980 census concluded that Chicago had 10 out of the 16 poorest neighborhoods in the US.[5] During this same time, Chicago suburbs boomed with the influx of successful white residents. White residents moved out of the city and to the suburbs, taking their strong tax base with them. As the emigration of whites to the suburbs continues so does the minority succession of inner city neighborhoods. As the succession over increasingly large urban areas continues, the problem of increasing tax burdens concurrent with a decreasing tax base arises.[6] This disinvestment in Chicago’s inner city is evident in the decline in income within Chicago whereas the suburbs saw a large increase in income from 1969 to 1979.[7]

The vulnerable African Americans living in the inner city suffered from changes to housing that came with this redistribution of wealth in Chicago. Major Richard M. Daley, elected in 1989, led an administration characterized by the weakening of community development and increased privatization.[8] Stacking his administration with supporters of his gentrification agenda, Daley was able to focus on more “affluent consumer markets” and paid no attention to the need for low-income public housing, causing the disappearance of “almost half of the housing units… since 1960”.[9] Daley’s administration upheld the stance that poverty is the result of either “the immigration order or a self-inflicted condition”.[10]

Chicago’s permanent underclass is a combination of many elements. The Daley administration’s inflicted gentrification not only displaced the urban poor, but also left poor African Americans vying for a limited amount of low-income housing. The slim amount of low-income housing, much of it dominated by gangs, left others living in a perpetual state of fear. The presence of gangs not only contributes to a sense of fear, but also causes rapid turnover of those living in gang-infested neighborhoods. The high housing and employment turnover within these communities subsequently hurts the economy of these areas. Economic stimulation is not consistent and jobs tend to be short-term and are often illegal in nature.[11] This type of environment creates an imprisoning cycle. Loretta J. Brunious wrote on this subject, focusing on the neighborhood of Englewood. Brunious emphasized that the prominence of gangs dictates much of the social structure of Englewood, contributing to a high crime rate and a distorted mental constructs of children regarding their community.[12] Many of these children growing up in Englewood join the gangs when they are old enough, never leave the neighborhood, and perpetuate the cycle.

The Heat Wave Itself

Temperatures from Chicago Midway Station July 1-17, 1995[Image Sources 1]

The Chicago Heat Wave of 1995 took place from July 12th to the 16th. The heat wave was declared a state of emergency on the 15th. The temperature reached 106 degrees Fahrenheit on July 13th, which was the warmest temperature for July recorded since 1928, which was the advent of temperature recording in the area.[13] The heat index reached up to 120 degrees. Streets cracked, cars broke down, buildings baked in the sun, and roads buckled.

Not only was heat an issue, but there was also the issue of high humidity, low wind, and high concentration of ground level ozone, leaving Chicago with a climate characteristic of the tropics. The level of humidity intensified the effects of the heat, making breathing more difficult especially for those with asthma or emphysema, which tended to be the elderly. Chicago citizens were urged to use air conditioners and pools. Those driving suffered from heat exhaustion while stuck in traffic.

They city experienced dispersed power outages due to the exceptional power demand and utilization. In some neighborhoods, fire hydrants were opened to cool people down, causing water consumption to rise twice as high as normal use for a summer day.[14] Water pressure fell as result of the high water usage. The heat wave in July 1995 in Chicago was one of the worst weather-related disasters in Illinois history.

More than 700 deaths are attributed to the heat wave, but the exact number is widely contested. Many more people became sick than the city was equipped to handle during this period. There were ambulance shortages that caused fire trucks to be dispatched during health emergencies. Hospitals quickly became overcrowded, leaving patients in critical condition without the help they needed. Those who perished due to the heat wave piled up in the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office, which was unable to handle the number of deceased .[15] Refrigerated trucks were utilized as additional storage until the medical examiner could get to them days after the temperatures dropped back into normal range.

Causes

NASA urban heat island visual. Rural areas do not absorb as much heat as urban areas.[Image Sources 2]

Urban Heat Island and Lack of Accurate Temperature Reporting[]

As classified by the EPA, an “urban heat island” is not actually an island in the topographical sense of the word, but in the sense of isolation, as characterized by the word. Urban heat islands are places that when compared to rural areas experienced very little nocturnal cooling, thereby leaving people at risk for heat-related health issues 24 hours a day. This intense heat is created by the high concentration of buildings, parking lots, and roads in urban areas, which tend to absorb more heat in the day, and radiate more heat at night when compared to that of rural sites. Official temperatures for the city of Chicago are taken at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, which is a more suburban location, and did not account for the increased absorption. The temperatures experienced by those in the inner city were not reported accurately.

Most of the victims lived in these inner city neighborhoods like Englewood, and experienced the effects of an urban heat island firsthand. From a meteorological standpoint, the urban heat island is the only factor that could be deemed partially responsible for the deaths in the inner city. However, the urban heat island factor, which at first glance appears to be solely meteorological, becomes a social factor because of its characteristic inner city location. The racial and socioeconomic makeup of the inner city, with its typically higher concentration of elderly, poor, African Americans, leaves the communities vulnerable and underrepresented.

Race[]

Of the communities with the highest death rates during the heat wave, one of which was Englewood, most had a population that was between 94 and 99 percent African American.[16] Race is more than a classifying factor when discussing the victims of the heat wave. Race changed the way many residents were affected. In predominately Latino communities the heat-related death rates were noticeably lower. Two explanations for this ethnoracial difference have been proposed in the context of the heat wave. The first explanation is that Latinos are more accustomed to the heat than African Americans. The second is Latino seniors benefit from a stronger support system than their African-American counterparts, which is evident in a crisis.[17] There is no biological evidence that Latinos are better equipped to handle the heat. However, the cultural argument is generally unsubstantiated as well.

One must examine the social anatomy of a community with particular emphasis on the support systems available to residents. Doing so would reveal a greater sense of support within low-income Latino-dominated neighborhoods when compared to low-income African-American neighborhoods.[18] Factors like the number of abandoned buildings, rate of violent crime, low population density, and activity within public life dictate the potential for heath-related deaths in the neighborhoods. There is an undeniable relationship between crime and neighborhood deterioration. It is essential to examine the “place-specific social ecology” that dictates the distribution of harm and how that harm is then racialized.[19]

Living Alone[]

Since the 1950s, there has been a noticeable demographic shift regarding the living conditions of the elderly. The proportion of elderly people living alone is steadily increasing and the proportion within Chicago is much higher than the national average.[20] Senior citizens living alone are more susceptible to become depressed, withdrawn, and fearful.[21] Many lack support systems of any sort. Englewood’s citizens are old and poor. Not only are the elderly, African-American residents of Englewood vulnerable due to this demographic shift, but there is a shift in the cultural condition as well.

Culture of Fear[]

The inner city breeds a cultural condition of fear. In 1995, among all U.S. cities with populations larger than 350,000 people, Chicago ranked 6th for robberies and 5th in aggravated assaults.[22] The presence of violence within Chicago as well as violence targeted at the elderly perpetuates a cycle of fear regarding one’s surroundings. According the 1996 Chicago Police Department’s Annual Report, there were more than 28,000 crimes committed against seniors in 1995 and more than 33,000 crimes committed against seniors in 1996.[23] The prevalent culture of crime against senior citizens, as well as the culture of fear that it breeds, makes those living in crime-ridden areas more reluctant to trust their neighbors, leave their houses or apartments, and causes them to exhibit avoidant behavior.

Not only was crime present on the streets, crime within senior housing had been rising steadily since 1988.[24] These various crimes include homicide, robbery, assault, and vehicle theft.[25] Constantly surrounded by fear, seniors would not open their doors in trepidation that those checking on them were there for harmful reasons. An elderly African American living in a low-income apartment building would have experienced something like this this fictionalized personal narrative:

For those of you who do not know Englewood, Chicago picture the worst neighborhood in your area, hear the gunshots, and feel the overwhelming anxiety that sets if you forget to lock your door.

In his one bedroom apartment in Englewood, Mr. Anthony Tyler is sitting on a cracked, polyester-fabric chair in the middle of the room. The building is located on 63rd Street, previously home to the notorious H. H. Holmes, one of the first publicized serial murderers in America in the late 19th century.[26]'

It is hot and unfortunately Anthony’s apartment building does not have central air conditioning, and with the rent already exceeding his tight budget he could not afford a window unit. The lack of cool air really creates discomfort in the middle of July.

Struggling to get out of the chair, Anthony waddles slowly over to the window with its peeling paint in need of a touch up.

“If only my landlord cared,” he thinks.

Peering outside of the apartment window he sees the fuzzy and distorted image that is the street, looking as though he is peering into an oven to check on a roast cooking. Anthony recognizes some of his unemployed neighbors standing on the corner with nowhere to go. They stand there almost every day, rain or shine.

The roving gang that usually ends up on his block is back -- looking to stir up some trouble. It is easy for Anthony to flash back to the days of bustling storefronts and a steady job. Now it seems like a distant memory.

The city is baking and has been doing so for the past three days, a conclusion that he has come to solely based on the constant sweat covering him since July 11th. No warning, no information, no air conditioning. Only fear.

Someone begins to knock on Anthony’s door. Fear of the identity of the person knocking on his door…Fear of the gang that usually hangouts outside of his building…Fear of the unknown.

The knocking subsides and he hears voices outside of the front door.

“Grab the arms and I’ll grab the legs!”

The voices sound strained.

Anthony has no idea who the voices belong to.

One of the voices belongs to Charles Henson. Henson is a neighborhood policeman assigned to Englewood during July. Henson and his partner’s strained voices are explained by their attempt to pick up one of Anthony’s neighbors. They are getting ready to carry her down the flights of stairs.

“No, no we can’t yet” they say, “There are no ambulances to transport the body.”

“I never heard her call out for help!” Anthony thinks to himself.

Sweat begins to drip from his brow. The sheer level of heat is unimaginable. So is the fear. Fear of what’s going on, and fear that he is going to end up like his neighbor.

The voices subside and feet shuffle down the one flight of stairs. Anthony is invisible.

Vulnerable. Alone. Afraid.

Warning Systems and the Failed Distribution of Information[]

The U.S. Department of Commerce commissioned a National Disaster Survey Report for the heat wave. Compiled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in December of 1995, the report provides insight into the effectiveness of governmental warning systems for a heat wave. It also explores whether the standards were met during the Chicago heat wave of 1995. The report provides an overview of information regarding meteorology, health impacts, and preparedness according to what the National Weather Service should have provided for the citizens of Chicago. The report finds that the National Weather Service is not to blame and that it followed all proper measures when reporting the heat wave and temperatures.

The NOAA report is flawed in that it is presenting information in a way that is favorable for the image of the government as opposed to the unseen population of elderly African Americans in Englewood. Additionally, the report was requested by the U.S. Department of Commerce, not the local Chicago government. Therefore, one can question if preparedness for natural disasters is a local or federal responsibility. Chicago officials were aware of the weather forecast in Chicago during the heat wave, yet there was no city protocol in place for relaying warnings, forecasts, or anything of the sort to city agencies. Consequently, the Chicago Department of Health was relying on information from the National Weather Service through the media.[27] This lack of proper distribution created a domino effect, leaving the Chicago Medical Examiner’s Office unaware of the incoming influx of bodies.

A lack of proper classification systems for heat waves and heat-related deaths was a detrimental issue during the heat wave. This lack of infrastructure for classification systems advances a technocratic, science-driven vision of disaster response, suggesting that information was improperly distributed during the heat wave. This is evident in Impacts and Responses to the 1995 Heat Wave: A Call to Action , which was published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Looking at the title of this report, “A Call to Action,” one might expect to read a report produced by the local Englewood government or neighborhood of the same poverty level angered about the lack of action during the heat wave, yet this report was produced by state climatologist and published for an audience of academics, researchers, scientist, or those employed in the meteorological field.

The three themes the report focuses on in reference to hazardous weather reporting are that “most people do not understand the relative danger of various weather conditions, statistics for weather-related deaths are often unreliable; and much weather-related loss of life is concentrated in a few events”.[28] As a reader it is difficult to grasp these general statements. When discussing the notion that people are unaware of danger, it not only removes blame from the institutions responsible for the distribution of information and places it on the individual, but it also raises questions of accountability. This lack of education about hazardous weather exposes issues in greater Chicago during the heat wave. Race and poverty affect access to education. Instead of targeting poverty as the root cause behind the lack of knowledge of those that are most vulnerable, the report simply advocates a technocratic approach of “continuing education and reminders when heat waves approach”.[29]

The report emphasizes a key finding that temperature and moisture conditions associated with the heat island should be determined and incorporated in preparing high temperature forecasts. Such an emphasis on data collection and quantitative materials continues to further the report’s scientific stance, which is not something that the vulnerable, poor, elderly in Englewood are going to accept as a valid reason for increased death within their community (if they are even able to see this report). Data are also inaccurate in reporting the number of heat-related deaths. The report points out a lack of classification for heat-related deaths. Blaming the data-reporting system bolsters the report’s stances as an academic report.

A small number of “weather catastrophes typically cause most deaths”.[30] The report then continues to claim that weather-related deaths have a physical linkage or can be “attributed to activities leading to death during the extreme event.” These statements place blame far away from the failings of the local, state, and federal governments to warn those who are the most vulnerable.

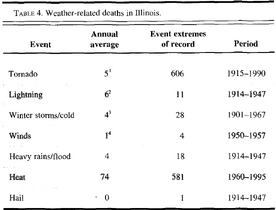

Weather-related deaths in Illinois from extreme events of record[Image Sources 3]

The approach fails entirely to recognize the racial and economic inequalities present in Chicago that left elderly, African Americans in the poor community of Englewood the most susceptible to heat-related deaths. When looking at the number of weather-related deaths in Illinois from 1960 to 1995 one can see that heat is responsible for 74 deaths with 581 extreme events on record, whereas tornados are responsible for five deaths from 606 events with dates spanning 1915 to 1990.[31] Clearly the system for preventing heat-related deaths is lacking. One must question why people were not aware of the heat wave and how to avoid its effects. However, the report only emphasizes the data as providing evidence for individual events contributing the most to the death toll associated with a type of hazardous weather event.

Interpretation of Photo[]

Charles Henson, an Englewood Police Officer, after removing a heat victim's body from the victim's apartment.[Image Sources 4]

This photo depicts Chicago Police Officer Charles Henson of the Englewood District. Henson is reported having removed a heat victim’s body from an apartment. This photo illustrates the overarching issue of poor resource allocation during the 1995 Chicago Heat Wave that affected the poor, mainly African-American neighborhoods of Chicago the most. This photo was entered into the Chicago Tribune’s archives on July 17th, 1995. The photo could have been captured at any point during the heat wave, but due to its later entry one can infer that it was taken at a later date.

As the heat wave continued, resources became more are more scarce. Henson is a police officer not a paramedic. During the heat wave, those living in neighborhoods with higher crime rates were afraid to open their windows. If the citizen did not have air conditioning in their apartment, the window was the only source of airflow. Being uncomfortable with opening the window placed these people at higher risk for heath-related illness and death. Also visible in the photo is the car on which Henson is leaning. The car appears to be much older than a 1995 model, which lends information about the economic status within Englewood. Henson is most likely leaning on the hood of a poor, elderly African American’s car because of the model’s date as well as the apparently flat tire that has not been repaired. If the owner had economic means to fix their car, it would have been much easier for the owner to get out of Englewood and go somewhere with a milder climate during this period.

This photo captures the true vulnerability of Englewood during this time. Henson is reported to have just removed the body of someone who died during the heat wave. In addition to doing a job that is outside of his usual job description, Henson is also not saving someone. The victim was either alone, leaving them completely vulnerable, or their emergency call or a call on their behalf was not responded to in a timely enough manner. Not only is a lack of paramedic resources being dispatched to the area evident, the lack of economic comfort of community members is also evident.

Legacy of the Heat Wave

Heat waves are not “glamorous” disasters. They fail to generate the startling images seen with other disasters and command public interest. The 1995 Chicago heat wave was omitted from dominant historical accounts of U.S. cities in the 1990s drawing a parallel with HIV reporting in the 1970s and 1980s. The evident human dimension to this disaster was not reported due to the unseen groups that were being most effected. The 1995 heat wave is the prime example of Paul Farmer’s “biological reflections of social fault lines,” in which disaster is unequally distributed, targeting groups that are most vulnerable in society.[32] Human inaction is responsible for the outcome of this disaster.

In 1995 more than 700 Chicago residents died in the heat wave, yet it remains anonymous in American history. The Chicago Defender published an article on July 19th, 1995, after temperatures had begun to fall. Titled “We must learn to do better in next heat emergency,” the article makes suggestions for widespread notification through the media of the “opening and closing times of the cooling centers.”[33] Additionally, the article urges the readership to view the heat wave as “everyone’s responsibility.”[34] If one thinks about other great disasters in American history, like Hurricane Andrew of 1992, the event is still remembered as a catastrophic weather event. Aside from the enormous property damage credited to Andrew, 65 fatalities were attributed to the hurricane. This lack in coverage of the Chicago heat wave was due in part to the invisibility of the victims prior to the heat wave as well as the sensationalized representation of the heat wave in newspapers. This sensationalization through the use of provocative photos of victims as opposed to in-depth reporting on the conditions that created the unequal distribution harm, transformed the heat wave into a lighter “summer” news story.[35]

Did anything change following the Chicago heat wave of 1995? No. In July and August of 2011, a heat wave hit the United States causing 65 deaths in the Midwest alone.[36] For the first time since 1995, temperatures in Chicago soared over 100 degrees for two consecutive days. The Midwest, which was hit unimaginably hard in 1995, was again unprepared. As the climate continues to change, hazardous weather events will become more frequent. Not only do infrastructural changes need to be made, but also the invisible victims must be brought to light and given the necessary tools to survive.

See Also[]

Examining Race, Class and Katrina

Image Sources[]

- ↑ “Chicago’s Temperature Records.” National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office.

- ↑ "Heat Island Profile." illustration, NASA. September 15, 2012. Accessed December 7, 2014. http://www.nasa.gov/images/content/411898main_heat-island-profile-full.jpg.

- ↑ Changnon, Stanley A., Kenneth E. Kunkel, and Beth C. Reinke. "Impacts and Responses to the 1995 Heat Wave: A Call to Action." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society: 1501.

- ↑ “Chicago Police Officer Charles Henson of the Englewood District is shaken after removing a heat victim's body from an apartment where two people died.”. photograph. Chicago. Chicago Tribune. July 17, 1995. Online. http://galleries.apps.chicagotribune.com/chi-120706-heat-wave-1995-pictures/. October 12, 2014.

References[]

- ↑ Klinenberg, Eric. Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 13.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 6.

- ↑ Klinenberg,Heat Wave, 85.

- ↑ Squires, Gregory D. Chicago: Race, Class, and the Response to Urban Decline. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1987), 4.

- ↑ Squires.Chicago. 24.

- ↑ Taub, Richard P., and D. Garth Taylor. Paths of Neighborhood Change: Race and Crime in Urban America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984, 142.

- ↑ Squires.Chicago. 41.

- ↑ Betancur, J. J. "Community Development in Chicago: From Harold Washington to Richard M. Daley." The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 594.1 (2004): 99. JSTOR. Web. 5 Dec. 2014

- ↑ Carter, Ovie. The American Millstone: An Examination of the Nation's Permanent Underclass. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1986, 257.

- ↑ Betancur, “Community Development in Chicago”,101.

- ↑ Carter, The American Millstone, 3-5.

- ↑ Brunious, Loretta J. How Black Disadvantaged Adolescents Socially Construct Reality: Listen, Do You Hear What I Hear? (New York: Garland Pub., 1998), Xii, Xiii.

- ↑ “Chicago’s Temperature Records.” National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office. July 21, 2014. Accessed December 4, 2014. http://www.crh.noaa.gov/lot/?n=chi_temperature_records.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 6.

- ↑ Johnson, Dirk. 1995. 179 dead in Chicago heat wave as national toll reaches 360. New York Times (1923-Current File), Jul 18.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 83.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 88.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 88.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 90.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 44.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 45.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 55.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Matt. “Chicago Police 1996 Annual Report”. 1996, 27.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 58.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 62.

- ↑ Gottesman, Ronald. "H. H. Holmes." In Violence in America: An Encyclopedia. New York: Scribner, 1999.

- ↑ Brown, Ronald. "Natural Disaster Survey Report July 1995 Heat Wave." 1995, 41.

- ↑ Changnon, Stanley A., Kenneth E. Kunkel, and Beth C. Reinke. "Impacts and Responses to the 1995 Heat Wave: A Call to Action." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society: 1497-1506.

- ↑ Changnon et all, “Impacts and Responses”, 1504.

- ↑ Changnon et all, “Impacts and Responses”, 1498.

- ↑ Changnon et all, “Impacts and Responses”, 1501.

- ↑ Farmer, Paul. Infections and Inequalities: The Modern Plagues. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1999. 5.

- ↑ Freedman, Andrew. "Heat Wave 2011: Humidity the Stunning Hallmark." The Washington Post, July 25, 2011. Accessed December 4, 2014. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/capital-weather-gang/post/heat-wave-2011-stunning-national-statistics/2011/07/24/gIQAJ1FcYI_blog.html.

- ↑ Freedman, Andrew. “Heat Wave 2011”.

- ↑ Klinenberg, Heat Wave, 233.

- ↑ Freedman, “Heat Wave 2011”.